Chiton

2021-12-18 Original Prompt Part 1

All right, finding an efficient path! Today’s puzzle is hard, not because it’s complex, but because you mostly just need to know The Best Way To Do This Sort of Thing. You either know it already or you don’t, so this is a hard one to just solve if you’re not familiar with the problem.

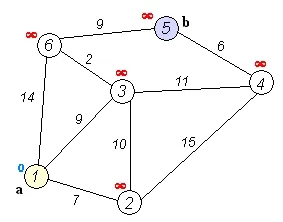

Today’s solution comes from Edsger Dijkstra, famed computer scientist best known for publishing Dijkstra’s algorithm. It finds the most efficient path between two nodes on a graph where distances can vary. Sounds pretty relevant, right?

This is the sort of thing I implemented back in college CS classes, but haven’t really looked at since. Luckily, Wikipedia has a description of the algorithm that I treated as a Great British Bake-off Technical Challenge (where contestants are given vague instructions about how to cook a thing and they have to interpret them as they go). So, I took a swing at it.

First we’ve got our helpers (which should look familiar):

from typing import DefaultDict, Dict, List, Set, Tuple

Point = Tuple[int, int]

# get grid boundaries and parse inputmax_x = len(self.input[0]) - 1max_y = len(self.input) - 1

def neighbors(loc: Point) -> List[Point]: res = [] x, y = loc # hard coded neighbors since there's only 4 for i, j in [(-1, 0), (1, 0), (0, -1), (0, 1)]: if not 0 <= x + i <= max_x: continue

if not 0 <= y + j <= max_y: continue

res.append((x + i, y + j))

return res

grid: Dict[Point, int] = {}for y, line in enumerate(self.input): for x, val in enumerate(line): grid[(x, y)] = int(val)That should look familiar at this point. We’re using the grid from day 11 where 0, 0 is the top left and x (the first item) increases to the right. I write that dang neighbors function so much that I should really incorporate a version of it into my base class.

Now it’s time for the algorithm itself! Let’s do it step by step:

- Mark all nodes unvisited. Create a set of all the unvisited nodes called the unvisited set.

I’m doing this backwards (starting empty and adding as we go), but it’s the same basic idea:

visited: Set[Point] = set()

- Assign to every node a tentative distance value: set it to zero for our initial node and to infinity for all other nodes. The tentative distance of a node v is the length of the shortest path discovered so far between the node v and the starting node. Since initially no path is known to any other vertex than the source itself (which is a path of length zero), all other tentative distances are initially set to infinity. Set the initial node as current.

from collections import defaultdictfrom math import inffrom typing import DefaultDict

start: Point = (0, 0)distances: DefaultDict[Point, float] = defaultdict(lambda: inf, {start: 0})target = (max_x, max_y)We’re using defaultdict again and doing 2 interesting things with it:

- we’re giving it a starting

dictthat includesstart(instead of starting from empty) - We’re using

lambdato populate the default. Let’s explore that for a sec

When we’ve used defaultdict in the past, we’ve used list or int as the first argument. The docs give us some context on what exactly that first argument (referenced there as default_factory) is, and what it does:

default_factory… is called without arguments to provide a default value for the given key, this value is inserted in the dictionary for the key, and returned.

So we weren’t just telling defaultdict what type we wanted to use as the default - we were giving it a function to call without any input. It just so happens that calling int() gives 0 and list() gives []. It’s the same thing we do when we initialize a set()! So for our case, we want the default to be math.inf, or infinity. It’s a useful “number”, because it’s bigger than everything. min(anything, inf) is always anything. For the purposes of this puzzle, we could also use a “sufficiently large number”, but we don’t know how long paths could be and it’s good practice to go big.

But, inf is a number and isn’t callable, so we can’t write defaultdict(inf). Instead we have to write a little function that always returns inf. lambda does exactly that. The syntax is a little concise. It starts with the word lambda, followed by 0 or more variables, a colon, and then what gets returned. Here’s a simple example:

add_one = lambda x: x + 1

# equivalent to

def add_one(x): return x + 1

# ---

give_inf = lambda: inf

# equivalent to

def give_inf(): return infIn our case above, our function takes no arguments (like defaultdict needs) and returns inf when called. Perfect!

- For the current node, consider all of its unvisited neighbors and calculate their tentative distances through the current node. Compare the newly calculated tentative distance to the current assigned value and assign the smaller one.

Ok, now we’re cooking. For each neighbor of current, its (tentative) distance from the start is the distance from start of the current node + the neighbor’s distance from current. The distance is tentative, because if we’ve looked at that neighbor from multiple angles, our current calculation might not be the lowest. If we’ve previously found a shorter path to that node, we don’t re-save our distance.

Here’s a good gif from Wikimedia that shows it in action. Watch it for a couple of loops and make sure you understand why each step happens:

Let’s implement it in some sort of loop:

current = startwhile True: for n in neighbors(current): if n in visited: continue distances[n] = min(distances[n], distances[current] + grid[n])

visited.add(current) # step 4So that’s step 3 - we’re looking at the neighbors and calculating the minimum path. We use grid[n] because the value at that point in the input is the distance. We also covered step 4 in that last block (mark the current node as visited).

There are 2 steps left, and we’re going to do them a bit out of order.

- select the unvisited node that is marked with the smallest tentative distance, set it as the new current node, and go back to step 3

To know which the smallest unvisited node is, we need to sort and filter the entire distances dict. We can squish that into a nice list comprehension:

current = sorted( [(d, p) for p, d in distances.items() if p not in visited and d != inf])[0][1]Let’s break it down:

- for each

(point, distance)indistances.items() - only grab paris where

pointis not invisitedand - only grab pairs where

distanceis notinf(meaning we’ve seen it before) - then, return a tuple of

(distance, (x, y)) - and sort that list of tuples

- once we’ve sorted, take the first element (at

0) and get it’s point (at1). That’s your new current!

Sorting a list of tuples is great - sorts by the first element and breaks ties using the second (and so on) element. We don’t actually care which point we look at in the case of a tie, but it’s nice to know the behavior’s consistent.

And then finally:

- If the destination node has been marked visited … then stop.

if current == target: return int(distances[current]) # because distances are technically floatsNicely done! That’s some classic Computer Science we’re getting to implement.

Part 1 Bonus

So I took a peek at part 2 and it’s the same thing, but the grid is much larger. Easy enough, but our algorithm was already a little slow (aka runtime was non-instant) in part 1 and it’s only going to get worse. The profiler tells us the culprit:

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function) 9998 1.692 0.000 1.692 0.000 solution.py:60(<listcomp>) 9999 0.222 0.000 0.222 0.000 {built-in method builtins.sorted} 1 0.031 0.031 1.960 1.960 solution.py:16(part_1)Our list comprehension on line 60 (where we filter down the entire distances.items()) is over 1.6 seconds; the next slowing thing is sorting that list, but it’s a huge dropoff. Instead of re-filtering and re-sorting every time, is there a way to maintain a sorted list as we go? Well if you scroll down the Wikipedia page, there sure is! It uses a “priority queue”, a data structure that always maintains its sort order when new items are added. Let’s do a quick re-write. The setup is largely the same, but we’ve declared a queue that begins life as [(0, current)] (aka (distance, point)).

Now we get to use a built-in package, heapq. It implements what we need for a priority queue for us! It’s called “heap-queue” because it uses a data structure called a “heap” under the hood. It’s not important to understand that, but you can read more about it in the docs if you’re curious.

Anyway, the functions we need are heappush and heappop, which add an element and remove the smallest one, respectively. The overall approach is similar:

from heapq import heappop, heappush

# same setup as before...

queue = [(0, current)]while queue: distance, current = heappop(queue) if current in visited: continue # now `current` is the closest unvisited point

# if the closest point is the target, we found it! if current == target: return distance

# otherwise, do the neighbors checks visited.add(current)

for n in neighbors(current): if n in visited: continue

potential_distance = distance + grid[n] if potential_distance < distances[n]: distances[n] = potential_distance heappush(queue, (potential_distance, n))That’s it! Note that we’re not removing anything from queue, which means there’ll be duplicates. That’s actually ok, because we’ll find the closest one first and ignore the rest (because of the if current in visited check). I gave it a run and we dropped from 1.97s all the way down to 0.04 seconds. Nice!

Part 2

For this part, our algorithm itself doesn’t change, just the way we generate the grid. So, I’ve refactored our grid parsing into a function that takes a multiplier. So, our final code is:

def _solve(self, grid_mult: int) -> int: grid, max_x, max_y = self.parse_grid(grid_mult)

# everything else is the same once we remove the old grid_parsing ...That parse_grid is similar to before, but with some additions. Here’s what we had before:

grid: Dict[Point, int] = {}for y, line in enumerate(self.input): for x, val in enumerate(line): grid[(x, y)] = int(val) # have to to all the places that this value shows up across the boardThis part isn’t too bad, but there’s a lot of chances for math mistakes. I decided to, when looking at each val place it all 25 times. To do that, we need to do that grid write operation for range(5) in 2 directions (and multiplied together for all the diagonals). Python’s got a great tool for this: itertools.product. It gives you every pair possible from the input:

from itertools import productproduct(range(3), range(3))# [# (0, 0),# (0, 1),# (0, 2),## (1, 0),# (1, 1),# (1, 2),## (2, 0),# (2, 1),# (2, 2),# ]Those are the multipliers we’ll use in each direction. Here’s the setup:

def parse_grid(self, grid_mult: int): for y, line in enumerate(self.input): for x, val in enumerate(line): val = int(val) for mult_x, mult_y in product(range(grid_mult), range(grid_mult)): ...And now, the math. The value itself has mult_x and mult_y added to it. We can’t quite use % 9 because that gives us 0 instead of the 1 we need. So it’s a little more involved:

out = val + mult_x + mult_yif out > 9: out = out % 10 + 1To be honest, I just played with adding 1 and using modulo until the numbers came out like I wanted. Lastly, we set the point, which is the max size (of the original input) multiplied by the multiplier:

...grid[(x + max_x * mult_x, y + max_y * mult_y)] = outFinally, we return the grid and our maximums for use back in _solve. All together:

def parse_grid(self, grid_mult: int) -> Tuple[Dict[Point, int], int, int]: max_x = len(self.input[0]) max_y = len(self.input) grid: Dict[Point, int] = {} for y, line in enumerate(self.input): for x, val in enumerate(line): val = int(val) for mult_x, mult_y in product(range(grid_mult), range(grid_mult)): out = val + mult_x + mult_y if out > 9: out = out % 10 + 1

grid[(x + max_x * mult_x, y + max_y * mult_y)] = out

return grid, max_x * grid_mult - 1, max_y * grid_mult - 1A bit of extra detail work today, but we got there! And knowing bout Dijkstra’s algorithm is always helpful.