Restroom Redoubt

2024-12-27 Original Prompt Part 1

Let’s move some robots! We’ll start with the quick-and-dirty approach I actually solved with, then we’ll do some refining as we go.

First up is an unusual feature: the grid size is different between the test and real inputs! Luckily, my Solution class has the mode available as a property:

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_1(self) -> int: if self.use_test_data: num_cols = 11 num_rows = 7 else: num_cols = 101 num_rows = 103That out of the way, we can parse some robots out of our input. Much like previous days, we can use regex to extract every number out of each line, since we know exactly where everything will be:

import re

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_1(self) -> int: ...

for line in self.input: col, row, v_col, v_row = [int(s) for s in (findall(r"-?\d+", line)]NOTE: despite the prompt using

xandyfor the coordinates, I stuck with myrowandcolcoordinates (as described on day 4), since I find that easiest to reason about. All that took was ordering the variable names a little differently.

In contrast to previous days, we have to ensure to include -? in our regex to account for negative numbers. That was a fun bug.

Anyway, now that we have the robots, we need to move them. The most basic approach is to add the robot’s velocity to its position, then modulo the size of the grid in each direction. Do that 100 times and we know where the robot lands.

Luckily, we can shortcut our repeated addition with a bit of multiplication! We can do all our steps at once and modulo a single time rather than wrapping after every step. That makes calculating each robot’s final position simple:

...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_1(self) -> int: ...

robots: list[GridPoint] = []

for line in self.input: col, row, v_col, v_row = parse_ints(findall(r"-?\d+", line))

updated_row = (row + v_row * 100) % num_rows updated_col = (col + v_col * 100) % num_cols

robots.append((updated_row, updated_col))Some quick spot checks against the test input confirm that our robots have landed in the expected locations!

Next, we have to divide the grid into quadrants. Because we know that our grid boundaries are odd, each dimension will have an exact middle equal to half of the size (rounded down). A robot in a quadrant will have coordinates that are strictly greater or less than each of those lines.

To count each quadrant, we nee every combination of < and > for both rows an columns; 4 quadrants in all. We reach once again for itertools.product:

from itertools import productfrom operator import gt, lt...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_1(self) -> int: ...

row_boundary = num_rows // 2 col_boundary = num_cols // 2

total = 1 for row_op, col_op in product([lt, gt], repeat=2): total *= len( [ 1 for r in robots if row_op(r.row, row_boundary) and col_op(r.col, col_boundary) ] )

return totalPart 2

Now we have to… find a Christmas tree? This is a new one. I’ll assume that we’ll know it when we see it. In contrast to part 1, we’ll need to be stepping our robots manually and Might as well do some cleanup before we get too deep into it.

Part 1 Cleanup

Because each robot is self-contained, it’s a good candidate for encapsulation. For part 1, our robot needs to be able to take a step and report its quadrant. That’s easy to wrap in a class:

from dataclasses import dataclass...

@dataclassclass Robot: num_cols: int num_rows: int col: int row: int v_col: int v_row: int

@staticmethod def from_line(line: str, num_cols: int, num_rows: int) -> "Robot": # unknown-length items go last to type checker doesn't complain return Robot(num_cols, num_rows, *parse_ints(findall(r"-?\d+", line)))

def step(self, distance=1): self.row = (self.row + self.v_row * distance) % self.num_rows self.col = (self.col + self.v_col * distance) % self.num_cols

@property def quadrant(self) -> int: row_boundary = self.num_rows // 2 col_boundary = self.num_cols // 2

for quadrant, (row_op, col_op) in enumerate(product([lt, gt], repeat=2)): if row_op(self.row, row_boundary) and col_op(self.col, col_boundary): return quadrant

return -1The implementations should look familiar based on our part 1 code. I went with a staticmethod for an alternative constructor to encapsulate turning a line into a Robot- the caller doesn’t need to know how that works. This is a common pattern in Rust code and, if you’re writing Python like it’s Rust, makes for nice constructors for dataclasses with lots of fields.

Back in our part 1 code, we can vastly simplify our approach:

from collections import defaultdictfrom math import prod...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_1(self) -> int: if self.use_test_data: num_cols = 11 num_rows = 7 else: num_cols = 101 num_rows = 103

quadrants = defaultdict(int) for line in self.input: r = Robot.from_line(line, num_cols, num_rows) r.step(100) quadrants[r.quadrant] += 1

return prod(quadrants[i] for i in range(4))That’s the whole thing! We can initialize, move, and locate our robots in a single pass now. We store how many robots report for each quadrant, then multiply them up at the end. I was especially proud of storing the hidden robots in -1. Because range starts at 0, we can skip them for free. Otherwise, we’d have to only store robots who reported a value or something, which would require extra conditionals and checks. This felt much more elegant. We also got to use math.prod, which is the multiplication equivalent of sum!

Part 2 For Real

Now it’s time to look for patterns in the noise! I wasn’t sure where to start, so I started simple: take a step and print the grid:

from collections import Counter...

@dataclassclass Robot: ...

@property def position(self) -> tuple[int, int]: return self.row, self.col

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_2(self) -> int: ... # declare boundaries robots = [Robot.from_line(line, num_cols, num_rows) for line in self.input]

for i in range(100): for r in robots: r.step()

locations = [r.position for r in robots] grid = Counter(locations)

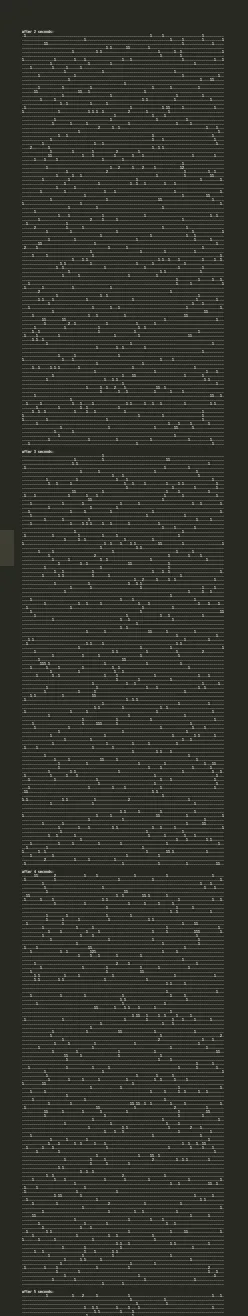

print(f"\nafter {i+1} seconds:") for r in range(num_rows): print("".join(str(grid.get((r, c), ".")) for c in range(num_cols)))This worked great for printing the grid! collections.Counter makes counting the robots at each location simple. But, the printed pages are so long (103 rows tall) that it was hard to get the perspective I though I’d need. So I tweaked my code to dump to a file instead:

from pathlib import Path...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_2(self) -> int: ...

images: list[str] = []

for i in range(100): ...

grid = Counter(locations)

print(f"\nafter {i+1} seconds:") images.append(f"\nafter {i+1} seconds:") for r in range(num_rows): print("".join(str(grid.get((r, c), ".")) for c in range(num_cols))) images.extend( "".join(str(grid.get((r, c), ".")) for c in range(num_cols)) for r in range(num_rows) )

print("\n".join(images)) Path(__file__, "..", "output.txt").resolve().write_text("\n".join(images))Then, I used VSCode’s minimap (which I usually have turned off, but was very useful here) to get a super zoomed out view of the pages:

Unfortunately, no Christmas trees; just a lot of random noise. I upped the number of pages to check from 100 to 1_000 and scrolled through them quickly but still nothing.

But, I did notice that about halfway through my first hundred pages, there was an image that looked like it was trying to be something.

SEVERENCE GIF NUMBERS

It’s not a tree, but you can clearly see there’s more something on the highlighted image than in the others:

Let’s go down this rabbit hole! We know that the vertical position of every robot will repeat every 103 seconds (since that’s how many rows our “screen” has). Instead of printing every page, let’s have our program print each page that shows that horizontal band (starting with the first):

...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_2(self) -> int: ...

START = 63 # for my input; yours is probably slightly different for r in robots: r.step(START)

for i in range(100): for i in range(1, 100): # our first loop is now the second step for r in robots: r.step() r.step(num_rows)

images.append(f"\nafter {i+1} seconds:") images.append(f"\nafter {START + num_rows * i} seconds:")

...Now we’re cooking! The only big change is that we’re stepping in multiples of the screen height and adjusting our starting position (and number printing) accordingly. Despite not knowing what to look for, after scrolling through these 100 images, something definitely jumps out:

The revealed puzzle image (click to show)

The page number directly above this image is our answer!

Part 2 (Programmatically)

While we’ve gotten our gold star, my goal for AoC is typically for the program to spit out the exact value I’m supposed to plug into the site. Our code gave us the answer, but we still had to go hunting for it, so let’s do one final pass.

Now that we know what we’re looking for, we can write a program to extract it. Looking at tree in all its glory, one interesting thing is that it’s comprised only of 1s. Most of the other pages have at least a few 2s and maybe even some 3s. I have a feeling that Eric included this unique property of the image page to help us find it. Let’s try out returning the first page with totally unique positions:

...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_2(self) -> int: ...

num_robots = len(robots)

for i in range(1, 100): if num_robots == len(set(locations)): return START + num_rows * iAnd there it is! Our puzzle answer once again.

Now the only manual part is telling part 2 where to START. Figuring we did part 1 for some reason, I printed out the safety score for each of the first hundred pages. And wouldn’t you know it, my vertical and horizontal bar pages were the safest! Assuming the vertical one always comes first (which I didn’t confirm with any other inputs), then we can do the entire puzzle, start to finish, in the (probably) general case with the following:

...

class Solution(StrSplitSolution): def part_2(self) -> int: ...

# find the "safest" page robots = [Robot.from_line(line, num_cols, num_rows) for line in self.input] pages: list[tuple[int, int]] = [] for page_num in range(1, 100): # our first saved page is page 1 quadrants = defaultdict(int) for r in robots: r.step() quadrants[r.quadrant] += 1

score = prod(quadrants[q] for q in range(4)) pages.append((score, page_num))

START = 63 # for my input; yours is probably slightly different _, START = sorted(pages)[0]

... # re-initialize robots here

for i in range(1, 100): for r in robots: r.step(num_rows) r.step(num_cols) ...

return START + num_rows * i return START + num_cols * iIt’s basically our part 1 code over-and-over. We could have reused some code here, but despite their similarity, part 2 and this block have pretty different goals. So, I’m happy to leave them as they are. We also started stepping by num_cols instead of num_rows, since the page with the “vertical” band (not shown, but looks similar) is the “safest”. Overall, I’m happy with how this turned out!

Lastly, there was some chatter on the subreddit about frustration around today’s puzzle. The instructions felt sparse and with less direction than we normally get. Ultimately, I liked it. We think of AoC as “write code to solve a puzzle”, but really it’s “solve a puzzle; writing code will probably help”. Today was definitely the latter case. I might have liked a little more direction, but we definitely knew it when we saw it, so I’m not too bothered.